School Nurse Second Victim

Medication Errors: The School Nurse as Second Victim

Stillwater, A. (2018). Medication errors: the school nurse as second victim, NASN School Nurse, 33(3), 163-166. Copyright © [2018] Ann Stillwater. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. doi:10.1177/1942602X7747294

Ann R. Stillwater, MEd, RN: Currently, Ann is the school nurse at the Capital Area School for the Arts Charter School in Harrisburg Pennsylvania. Ann has been providing nursing services in schools since 1993, and has special interests in encopresis, resiliency, democratic schools, and the intersection of science and spirituality.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to thank the nurses who shared their stories, the reference librarians of High Library at Elizabethtown College, and JD Stillwater, Amanda Dewey, and Cynthia Galemore.

Abstract: Medication errors occur in the school setting as they do in other healthcare settings. In this article, three accounts of school nurse medication errors are presented. School nurses often undergo emotional trauma after a mistake is made. Other fields of healthcare are incorporating the second victim phenomena in their responses to errors, with the patient as the first victim, and the caregiver who made the mistake as the second. Researchers have identified six stages of the second victim’s journey. School nurses and administrators would benefit from understanding and utilizing this model.

Keywords: school nurses; National Association of School Nurses; medications; policy and procedures; political/legal; staff development; professional issues; second victim

Main Document:

As early as 1914, Maxwell and Pope in

Practical Nursing: A Text-Book for Nurses,

urged: While measuring medicines, never think of anything but the work at hand and never speak to any one nor allow any one to speak to you

(p. 431). This is excellent advice for the ideal situation, but school nurses have myriad interruptions, and medication errors do happen. Nurse researchers Trieber and Jones explained this dynamic eloquently:

As human beings, nurses make errors. Like other health providers, they work in environments that have become increasingly technical, complex, and chaotic, and thus, more amenable to error. Nurses learn that safe medication administration is an individual responsibility and that the blame for errors ultimately rests with the person administering the drugs. Accurate administration of medications is such a deeply embedded principle of nursing that making these errors threatens the professional self, jeopardizing both identity and livelihood. It also means potentially harming another human being, thus violating the medical ethic to do no harm.

Yet, it is important to understand that nurses often deal with such mistakes and still continue to care for patients (2010, p 1327-8).

Despite studies suggesting that approximately 50% of those giving medications in schools have had a medication error (McCarthy, Kelly & Reed, 2000: Farris, McCarthy, Kelly, Clay & Gross, 2003) there is surprisingly little research on the subject. Richmond explained that there is limited relevant statistical data, due, in part, because medication error reporting systems and statistical data regarding medication errors in the school setting are limited

(2011, p. 305).

Simmons pointed out, School nurses assume a unique professional role because they stand astride the realms of education and health care

(2002, p. 87). This author hypothesizes that the paucity of studies stems from several factors including the dual education/medical loyalty Simmons pointed to, the fact that many school nurses are supervised by educators who lack formal medical training, lack of a clear, universally accepted definition of a medication error, professional embarrassment and emotional trauma that often accompany medication mistakes, lack of a standardized medication error reporting system, and punitive error-reporting systems.

The few studies that have been done provide some helpful information. McCarthy et al. (2002) and Farris et al. (2003) found that approximately 80% of admitted errors were a missed dose, 19-30% involved failure to document a medication that was given, and 15-20% gave a medicine without proper authorization. McCarthy et al. report that 22% gave an overdose or double dose, and 20% gave the wrong medication. Farris et al. found that 3.3% of errors were an extra dose, and 4.3% were the wrong medication. Some types of medication errors are significantly more common than others.

This author’s own medication error was emotionally devastating. The journey back to professional confidence included a desire to hear stories of other school nurses’ medication errors. Through connecting with other school nurses who made mistakes, perhaps there would be healing. A literature search led to the affirming description by Trieber and Jones, above, and additional supportive articles from other branches of nursing and medicine. It also revealed a need for more attention to medication errors in school nursing research.

Voluntary Case Studies

The author recruited participants through a post on the School Nurse Net, NASN’s All Member Forum, and in-person discussions of the project with local nurses. The author requested confidentiality regarding patient data, and assured confidentiality for nurses who participated. The NASN School Nurse Net on-line forum has over 16,000 members (2017). Only two responded with offers to provide personal stories. A third nurse responded with an offer to supply stories of medication errors of others. Several reminders were sent to the two willing to be included, and ultimately one withdrew, admitting that despite confidentiality assurances, the story was too raw to share. The other nurse who did participate admitted some anxiety about sharing, since the uncomfortable emotions were re-visited.

Results

Following are three accounts of medication errors in the school setting shared by the two nurses (including the author) who participated.

It was the end of the school day at the end of my first month at a new school. I had to cover the health suite for the last 30 minutes after sending my health assistant home earlier for health reasons. My 4 diabetic students came in to test glucose prior to dismissal. The 5th grader was running a little high at 250, so I sent him to check his urine just to be certain while I was tending to the others. The next day, I received a call from my nursing supervisor after she received a call from an irate father who said I made the student check his urine–something he had never had to do. With my supervisor, we reviewed the diabetic order which said, “test urine if above 250 and if nauseous and/or vomiting.

In my haste, I overlooked the preprinted check next to if nauseous and/or vomiting

. I had to write it up as a med error

for review. My supervisor then criticized me and reported to this irate father that I had not followed doctor’s orders

and would be reprimanded. It was brought up in my annual evaluation as a negative and an example that I did not follow nursing procedures.”

It was a typically busy day in the nurses’ office, but I was reeling from news of something outside of school. All day, I felt odd, distracted, and it seemed strange to be going about the usual routine. A student came in for a daily medication. I reached for the student’s medication bottle and also thought about the next student who would come later. I gave the pill, and returned the bottle to the cabinet upside down – our system to show that the med was given. It was only when the next student was getting medication that a sinking feeling came over me, finding the student’s bottle already upside down. I had given the previous student the wrong medicine! Luckily the student was ok and the parents were kind, but it was a profound shock to me personally and professionally, sapping my self-esteem and shaking my confidence. For several days I lived in terror of the administration’s reaction. There was no formal discipline for this med error, and the district began standardizing medication administration, placing the pill bottle in a manila envelope with the student name, birth date, and picture, to help avoid future errors.

Six 4th graders thought they needed their inhalers after recess on a high pollen count day. One, rarely seen in the health suite, was in the most distress with retractions and difficulty speaking even after hydrating. I gave him one round of his prescribed inhaler after checking his order. It wasn’t helping after 10-15 minutes. As continued my assessment , the distressed student’s parent called. She happened to be at his doctor’s wanting to update the student’s soon to expire albuterol prescription. I received the verbal order with “good timing

and was able deliver an additional 2 puffs. The conversation ended with the parent saying she would come to pick up her child and take him back to the doctor. The student was responding well to the albuterol as the parent arrived. She immediately remarked that this was not her child. I had mixed up 2 students with the same first name and last names. The parent was very understanding because she said even the teachers

mix them up. We quickly called to inform the doctor who had given me the verbal order, and then called the other child’s doctor and parent. Needless to say, my head was reeling. A very understanding nursing supervisor reviewed the situation with me, understood where I made my mistake, what I did to correct it, and acknowledged that I was placed in a situation where a mistake like that could easily be made. There was nothing punitive save for writing out the medication error

. I relabeled the bags that held the meds and spelled out verify the student

on the medication order with a name alert.”

Second Victim

These incidents are so disparate that the author had difficulty finding common themes. Since the three nurses experienced emotional difficulty, the author focused on the feelings after the error. Academic research on school nurses healing emotionally after a medication error was not fruitful. A broader search of medical literature revealed studies about the second victim phenomenon.

Other healthcare settings have begun to utilize the concept of the second victim, first named by Dr. Albert Wu in 2000. While the patient is the first victim, the healthcare practitioner who makes a mistake is the second victim, due to the emotional trauma of harming a patient and fear of possible legal and administrative sequelae. As early as 1991, Wu, Folkman, McPhee & Lo described the guilt and shame that resident physicians experience as a result of errors. They explained, mistakes are inevitable in clinical medicine

(1991, p. 2093). To maximize learning and support the clinician, they exhorted supervising physicians to respond sensitively

(p. 2093) to their distress.

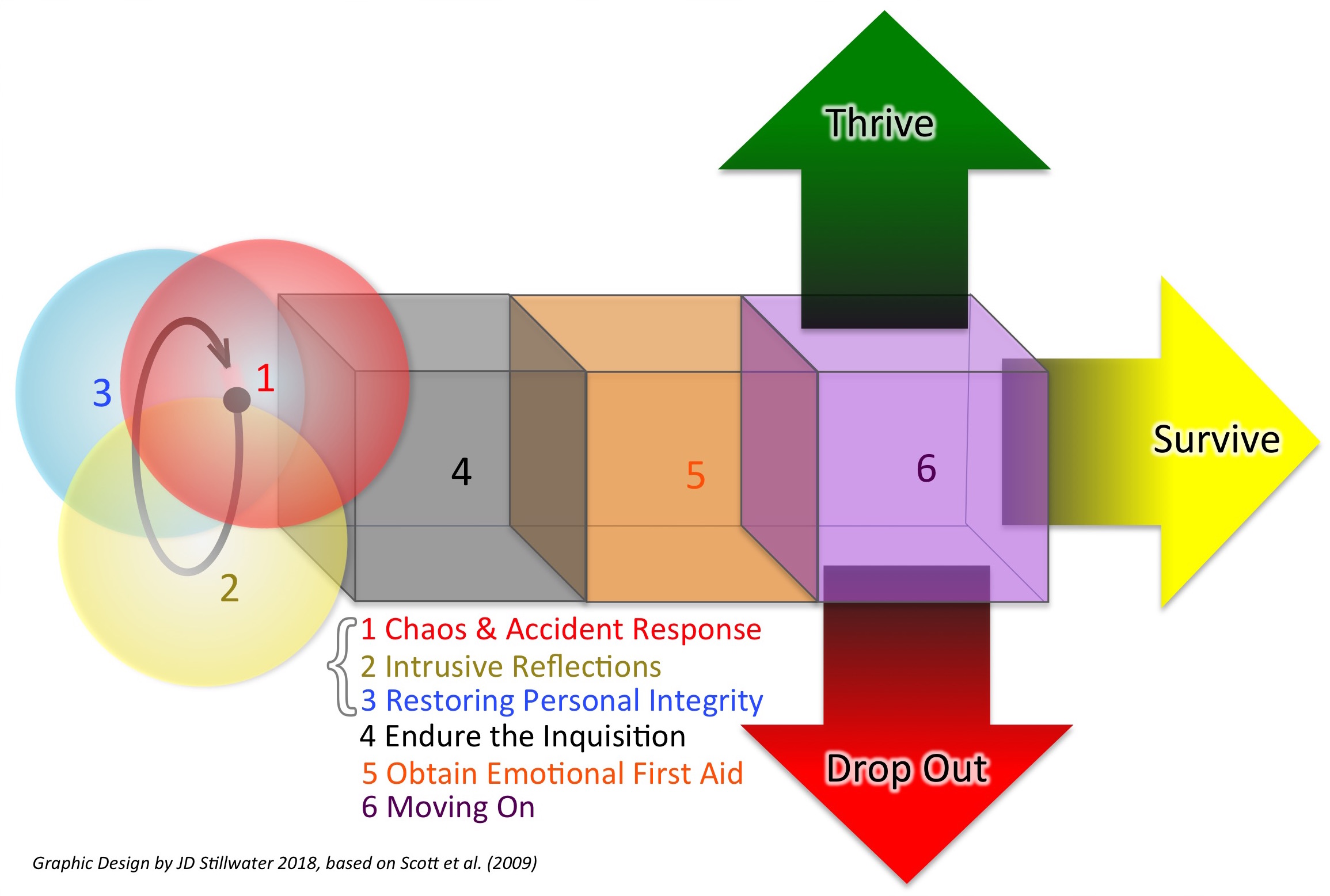

Scott et al. (2009) studied second victims’ experiences and described six specific stages (See Figure 1). The first three stages comprise impact realization and may occur simultaneously or the second victim may jump between them. Initially there is chaos and accident response as the error is discovered and mitigation actions begin. This first stage is characterized by both external and internal turmoil. The second stage, intrusive reflection , includes self-isolation and haunted re-enactments, often with an intense sense of internal inadequacy. Restoring personal integrity is third, with second victims finding trusted colleagues or friends in which to confide. This is also the stage where second victims return to work amidst possible gossip about the adverse events. Additional complications include privacy and legal concerns, which may limit what the second victim feels is appropriate to share.

Enduring the inquisition , the fourth stage, often intensifies professional doubt, as the institution investigates the error. The second victim may worry about professional licensure, job security, and possible litigation. The fifth stage, obtaining emotional first aid , focuses more deeply on the healing process. Confidentiality concerns often muzzle what second victims share with loved ones and peers. They may seek help through professional counseling, since institutions often do not identify where second victims can find help.

The last stage described by Scott and his colleagues, moving on, has three possible outcomes: dropping out, surviving, or thriving. Some second victims drop out and change employers or professions due to the trauma of the incident. Others survive, remaining in their positions but continuing to be haunted by the adverse event. Those who thrive manage to find and/or create some good from the incident and continue in their profession, stronger and wiser.

Many practitioners become experts in the area of the error as a way of moving on (Plews-Ogan, Owens, & May, 2012). Understanding these stages can provide structure for a difficult and chaotic journey after an adverse event.

These stages are similar to Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief. Just as those who are grieving may take a convoluted journey through their grief towards greater integration, second victims may not take a straight path through the stages described above. The author found this to be the case, and feeling stuck in the survival stage led the author to circle back to some of the earlier stages, which led to this research and discovering the stages!

There is a growing awareness of second victims in health care. Some nursing students today are educated about this concept (Amanda Dewey, personal communication, August 14, 2017). Safe Practice 8 of the National Quality Forum specifies very detailed guidelines in caring for second victims in a variety of healthcare settings (2010). Health care practitioners can learn about second victim issues through workshops held by The Center for Patient Safety (2017). Physicians created a peer support group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital after at least one of them experienced an adverse event (Plews-Ogan et al. 2012; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 2016). Johns Hopkins Hospital implemented a support program after a particularly difficult adverse event with a pediatric patient (Edrees et al. 2016). A 1999 adverse event led to the creation of the Medically Induced Trauma Support Services (MITSS), which has a hotline and on-line manual for organizations to create their own support services (MITSS, 2017). Ultimately, Addressing the needs of health care’s second victims needs to become part of national and local patient safety and quality improvement initiatives

(Seys, et al, 2012, p. 156).

School Nursing Implications

As of August of 2017, searches on Ebsco and Sage Journals yielded no articles in the literature about school nurses and the second victim phenomenon. It is time for school nurses to break the silence. In keeping with safe-practice advances in other healthcare settings, school nurses must educate each other and their administrators in decreasing the stigma around medication errors. Most second victims struggle professionally and personally in isolation, and the organization suffers along with the victim (Seys et al. 2012). A standard definition for school nurse medication errors, and creating and standardizing reporting systems for medication errors in schools, would allow a common data set for future study. The creation of non-punitive medication error reporting systems would increase reporting. Most importantly, utilization of existing services or the creation of school nurse second victim support groups would be more likely to ameliorate the emotional trauma after medication errors. Consideration of the second victim phenomena could be the impetus needed to increase study of school nurse medication errors and ultimately, create a safer environment for our students.

In closing, the words of Sheila Doss-McQuitty, President of the American Nephrology Nurses Association, writing in Nephrology Nursing Journal, also are apt for school nurses:

I encourage each of us to be there for our colleagues, remembering that errors can happen at any time by and to each of us. Second victims are no different from any of us – they just made an unintentional and unfortunate error. Instead of blaming, shaming, and abandoning, we need to address the impact on the caregiver who made the error while remembering that rarely is it due to intentional negligence or malice. Let’s be there for our colleagues and for ourselves.

(2016, p 462).

References

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, The Center for Professionalism and Peer Support. (2016). Peer Support. Retrieved from: http://www.brighamandwomens.org/medical_professionals/career/cpps/PeerSupport.aspx.

Center for Patient Safety (2017). Retrieved from http://www.centerforpatientsafety.org/second-victims/

Curators of the University of Missouri. (2017). ForYOUteam, caring for caregivers. Retrieved from

Doss-McQuitty, S. (2016). President’s Message: Second victim: do you know or have you ever been one? Nephrology Nursing Journal, 43 (6), 461-2.

Edrees, H., Connors, C., Pain, L., Norvell, M., Taylor, M., & Wu, A.. (2016). Implementing the RISE second victim programme at the Johns Hopkins hospital: a case study. British Medical Journal Open. 6(9): e011708 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5051469/ .org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011708 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011708.

Farris, K., McCarthy, A., Kelly, M., Clay, D. & Gross, J. (2003). Issues of medication administration and control in Iowa schools. Journal of School Health, 73(9), 331-337.

Maxwell, A. & Pope, A. (1914). Practical Nursing: A Text-Book for Nurses (3rd ed). New York: The Knickerbocker Press.

McCarthy, A., Kelly, M. & Reed, D. (2002). Medication administration practices of school nurses. Journal of School Health, 70(9), 371-376.

Medically Induced Trauma Support Services. (2017). Our history. Retrieved from http://mitss.org/about-us/our-history/

National Quality Forum. Safe practices for better healthcare—2010 update: a consensus report [website], 2010. Retrieved from http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2010/04/Safe_Practices_for_Better_Healthcare_–_2010_Update.aspx .

Plews-Ogan, M., Owens, J. & May, N. (2012). Choosing Wisdom: Strategies and inspiration for growing through life-changing difficulties. West Conshohocken: Templeton.

Richmond, S. (2011). Medication error prevention in the school setting: a closer look. NASN School Nurse, 26(5) 304-308. doi: 10.1177/1942602X11416369

Scott, S, Hirschinger, L, Cox, K, McCoig, M, Brandt, J, & Hall, L. (2009) The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider second victim

after adverse patient events. Quality and Safety in Health Care (18), 325–330. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.032870

School Nurse Net. (2017) Retrieved from https://schoolnursenet.nasm.org/communities/communities-home/community-members?communitykey= 36de

Seys, D., Wu, A., Van Gerven, E., Vleugels, A, Euwema, M., Panella, M, Scott, S., Conway, J., Sermeus, W, & Vanhaect, K. (2012). Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systemic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 36(2) 135-162. doi:10.1177/0163278712458918

Simmons, D. (2002). Autonomy in practice: a qualitative study in school nurses’ perceptions. The Journal of School Nursing, 18(2), 87-94.

Trieber, L. & Jones, J. (2010) Devastatingly human: An analysis of registered nurses’ medication error accounts. Qualitative Health Research 20(10) 1327-1342. doi: 10.1177/1049732310372228

Wu, A. W., Folkman, S., McPhee, S. J., & Lo, B. (1991). Do house officers learn from their mistakes? The Journal of the American Medical Association, 265, 2089–2094.

Wu, A. W. (2000). Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. British Medical Journal, 320, 726–727.